(Original: 1985 - Last updated 25 October 2025)

Select the underlined to read the associated monograph

Monographs

100 Earliest known map, a town plan from Catal Hyük, 6,200 BCE

l00A Clay tablet from Ga-Sur, 2,300 B.C.

100.2 Saint Belac stone slab, 2100 B.C.

101 Mesopotamian city plan, Nippur District, 1,500 B.C.

102 Turin Papyrus, 1,300 B.C.

103 Babylonian day tablet, world picture, 500 B.C.

104 Time Chart of Historical Cartography: Antiquity, 600 BCE to 300 CE (Raisz)

105 Ancient Greek views of the earth, reconstructed from description in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey

106 Three views of the earth from ancient Greece: Thales of Miletus, Anaximander, and Hecatæus (reconstructions)

107 Anaximenes of Miletus, world map, 610-546 BCE (reconstruction)

108 Hecatæus’ world map, circular disk, 500 BCE (reconstructions)

109 Herodotus’ world map, 450 BCE (reconstructions)

110 Ephorus’ Parallelogram, 350 BCE (reconstruction)

111 Dicæarchus of Messana, a world map, 300 BCE (reconstruction)

111.1 Qin Maps, 239 B.C.

112 Eratosthenes’ world map, 170-190 BCE (reconstruction)

112.1 Han Maps, 168 B.C.

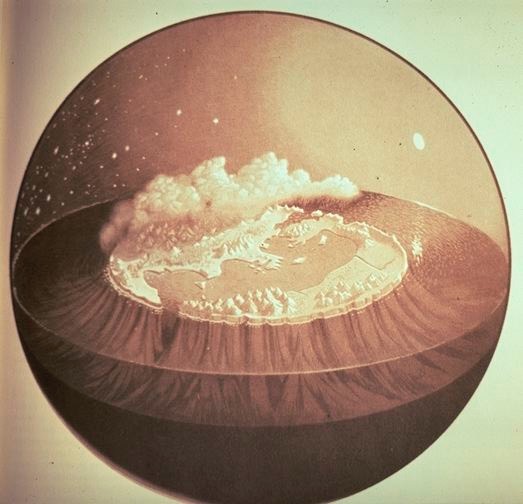

113 Crates’ globe, 180-150 BCE (reconstructions)

113.1 Ancient Chinese

world view, from the Chhin-Ting Shu Ching T’u Shuo, 138 B.C.

114 Posidonius’ world map, 150-130 BCE (reconstruction, Bertius, 1630)

115 Strabo’s world map, 18 CE (reconstructions)

116 Pomponius Mela’s world map, 37-42 CE (reconstruction)

117 Dionysius Periegetes’ world map, 124 CE (reconstructions)

118 Agrippa’s Orbis Terrarum, 100 CE (reconstructions)

119 Claudius Ptolemy

120 Tabula Peutingeriana, 100

121 Masada Map of Palestine

40+ relevant articles in .pdf format a list of articles available upon request

One of the foremost geographers of the 20th century, Professor Gaetano Ferro1 (1925-2003), late Professor of Geography and President of the Italian Geographical Society, wrote in 1996 the following: Cartographic documents of the past cannot be adequately studied and understood unless one first takes into account the culture that they express (and the methods by which they were constructed), on the one hand, and the aims and objectives for which they were intended, on the other. In other words, the depiction of the earth, and its evolution, are part of a system of thought and communication that is tied to, and a function of, the different eras and their means of expression. Within this perspective it is possible to overcome the ancient and deep-rooted habit of appraising the cartographic document of the past only according to whether it corresponds to geographic reality as we know it today, or better yet, whether it conforms to the mathematical rules of modern science, which governs how such a reality is to be represented.